In March’s blog post, we feature an interview with Dr. Kevin Painter, Professor of Mathematics, Politecnico di Torino.

When did you first become interested in mathematics and biology?

I always enjoyed both maths and biology growing up, but at school you view these as distinct subjects, to be studied separately. I imagine the following will be common for many in the field, but it hadn’t occur to me that “Mathematical Biology” existed as a thing until seeing it as an undergraduate option. At that time there were probably only a dozen or so universities across the UK with any significant presence in mathematical biology, and probably not that many more that were running a course in mathematical biology. An alternative choice of university, and I may have gone down a completely different path. Perhaps by now I would have solved the Riemann Hypothesis instead? Probably not. I’m lucky that math biology appeared on my radar when it did.

Was the decision to do a Ph.D. an obvious and easy choice?

I didn’t really know what a Ph.D. was at the start of my undergraduate degree, just dimly aware that members of a strange species called “postgraduate” were hovering around the place. The final year of my undergraduate degree, though, involved a yearlong research project (“Frequency selectivity in the cochlea”) and I started to read research articles and engage with mathematical models. This was great! With the alternative being a grown up job and entering the real world, it dawned on me that this Ph.D. thing could allow me to carry on playing for at least another few years. At that point, the decision to start looking around for a Ph.D. was easy.

What are your main research questions and why are they interesting?

We are extraordinarily lucky as mathematical biologists, in that the methods we employ can be adapted to such a broad range of problems. So while my Ph.D. explored the classic mathematical biology problem of embryonic morphogenesis (a topic I continue to love) I’m now involved in range of problems that extend to navigation of whales through noisy ocean environments and the dynamics of alpine snow melt. Each, of course, has its own key question and note of interest, but the unifying theme is the way things interact with themselves and/or their environment to become organised. It is the very ubiquity of these phenomena that make them so interesting.

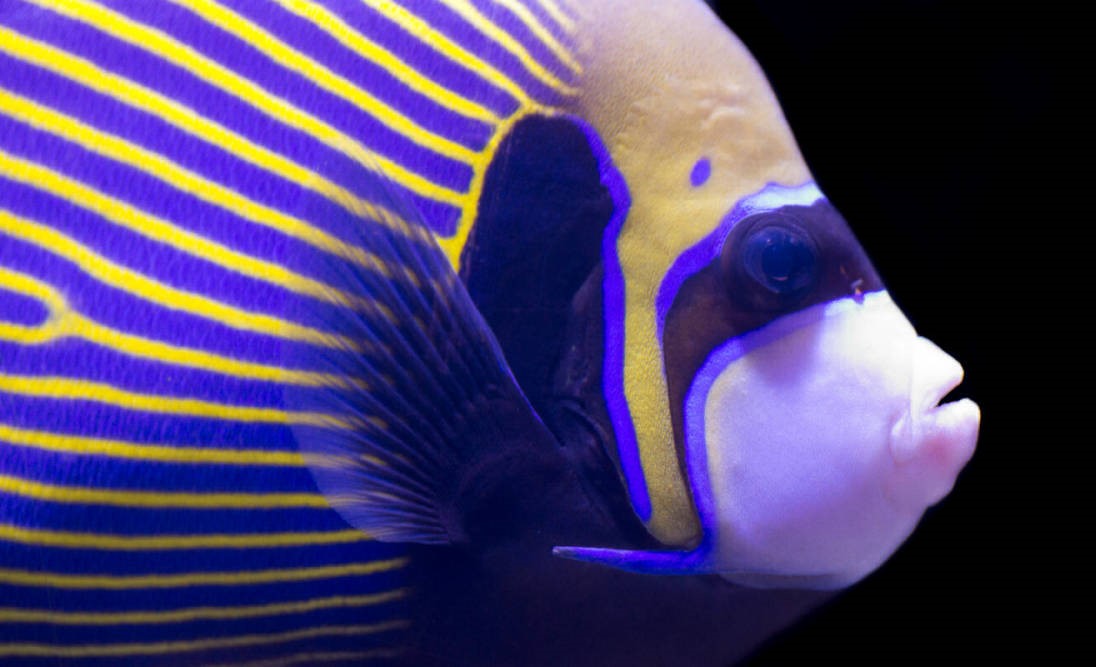

What kicked off my interest in pattern formation – the Emperor Angelfish (Pomacanthus imperator)

What makes you passionate about your work?

The feeling that new ideas can suddenly sprout from anywhere. On holiday a few years ago we were hiking near the summit of Etna which, being so active, is completely devoid of vegetation. So why could I see so many butterflies? An entomologist I met later suggested that it could be a case of “hilltopping”: grouping at summits to find a mate and an example of how landscapes can structure a population. This was the spark for a new research problem, which led this way and that way etc, etc. While the majority of our ideas, unhappily, lead nowhere, occasionally something emerges from the blue and opens up a new vista.

What is a typical work day/week like?

Hmmm. Since Covid, what exactly does “typical” mean?

Do you have any advice for someone considering a career in mathematical biology?

Collaborating with biologists and working at the interface between mathematics is biology is fascinating, rewarding, inspiring, exciting, stimulating, and … frustrating! Time moves differently in biological research and experiments can be fickle. Some of the interdisciplinary papers I’ve worked on were rooted in experimental work initiated more than half a decade previously: not a problem if you are well established, but less convenient for a young researcher trying to publish and find a job! So, get involved in interdisciplinary work – it will be all of the above superlatives – but keep your independent research going so that you don’t have to exclusively rely on the results of the next set of complicated experiments going the right way…

What do you like to do in your spare time outside of work?

My son is currently obsessed with birds (along with all things nature). So at the moment we are out hiking most weekends armed with cameras and binoculars. I miss many things about my previous home of Edinburgh/Scotland, but hikes in the countryside in February tend to be less damp now that I’m in Italy… Beyond that, I’ve really missed sitting in a cinema these last couple of years.

Any final comments or advice?

I find it amazing when I think how much math biology has grown just in the two and half decades since my Ph.D. So much so, that we have formed SMB subgroups in Cell and Developmental Biology, Mathematical Oncology, etc, etc. This growth has been an overwhelmingly positive thing, of course, but one downside has been the time to explore research outside your own field: it is hard enough to keep up with developments in your own area. Yet, the possibility of translating models and techniques across fields offers a wonderful opportunity, so I always try to find as much time as possible to engage with research outside my comfort zone.