In this blog post, we feature an interview with Dr. Mindy Liu Perkins, a postdoctoral fellow in the European Molecular Biology Laboratory, Heidelberg.

When did you first become interested in mathematics and biology?

I came to biology first, through a childhood love of dinosaurs and unusual animals. I didn’t dislike mathematics, but I didn’t actively begin to enjoy it until high school, when I took my first calculus class. Somehow I was drawn to the abstraction, the idea that integrals and derivatives describing physical phenomena could come out of an essentially philosophical analysis of hypothetical objects. By the time I applied to college, I had decided engineering was a logical field of study for me to blend math and logic with real-world applications. I selected electrical engineering as my major, where I gravitated toward the subfield of signal processing. Nevertheless, I was pretty certain I wanted to continue with life sciences somehow, so I ended up contacting a Ph.D. student who was working with bats (my favorite animals) to ask whether she would be willing to mentor an undergrad for research. She took me on initially just to stain some blood samples for her, and then she ended up becoming a fantastic mentor for my Bachelor’s thesis. With her support I developed a project to analyze the consequences of acoustic interference for echolocating bats using theory from signal processing. After I started that project, it just wasn’t a question for me that whatever I did next would also have to involve both mathematical analysis and biological systems.

What are the main biological research questions that you are interested in?

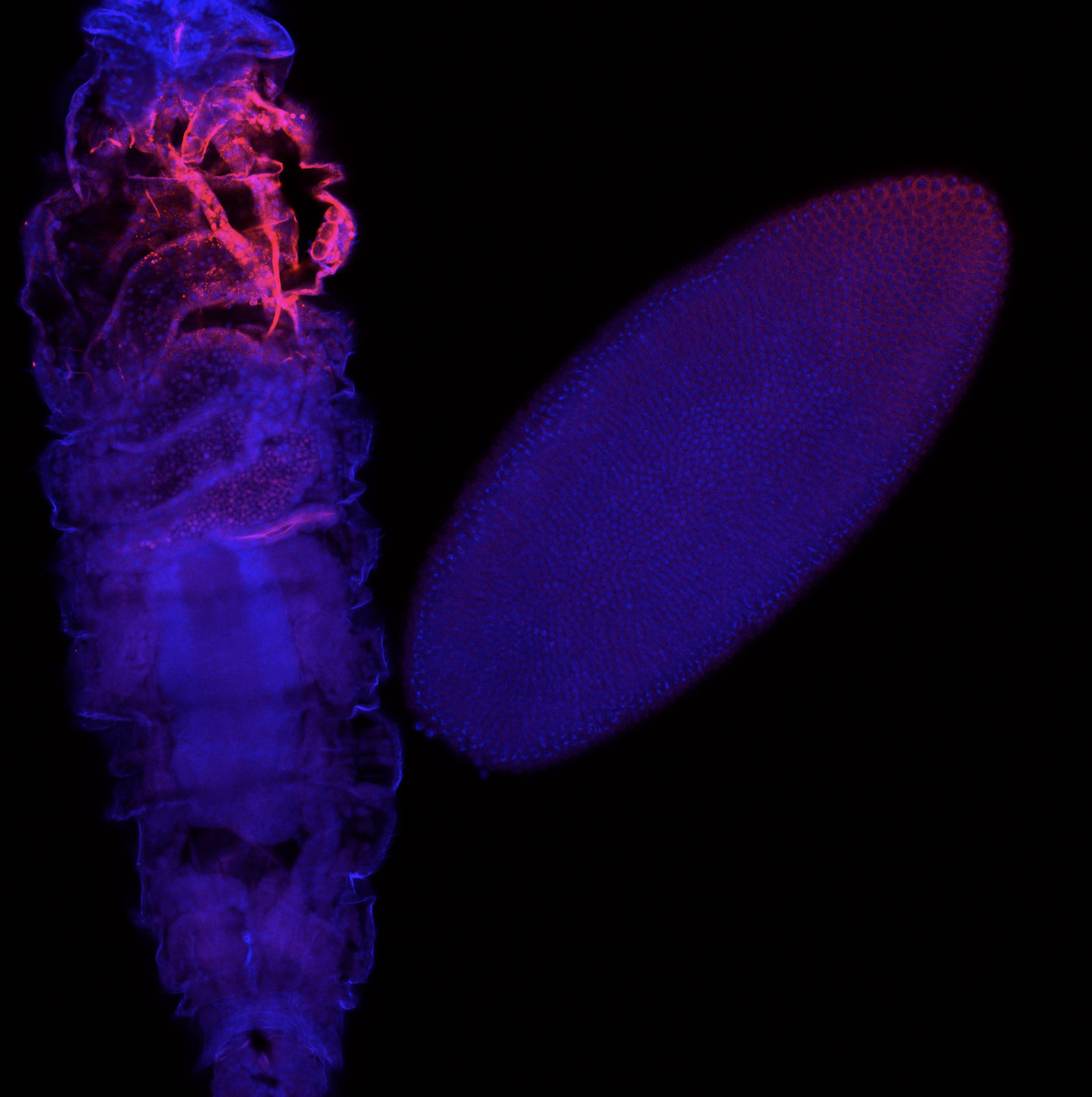

A fruit fly embryo (right) and larva (left) stained for a particular protein (red). The blue stain is meant to help identify the nucleus.

Since graduate school, my research has focused on understanding, from a mathematical perspective, how gene expression patterns like checkerboards or stripes emerge in groups of cells. What role does cell-to-cell signaling play in pattern formation? How are earlier patterns used to instruct the formation of later patterns? How does this relate to the mathematical properties of the underlying genetic networks? How is a multicellular pattern affected by the underlying dynamics in single cells, for example, the speed with which individual genes can turn on and off? How do we distinguish stochastic from deterministic contributions to patterning? I’ve used mathematical modeling from dynamical systems and control theory to investigate these phenomena in various setups in synthetic and developmental biology.

What types of questions do you think will be important to answer in the future in your field?

The literature on patterning in developmental biology often involves discussion of robustness, meaning that a growing embryo can still produce a normal adult even under a range of perturbations. In many cases, however, it’s been quite difficult to quantify robustness. I’d argue we can’t even really define the “robustness” of a system without first developing a clear understanding of the function that system is meant to fulfill. This seems like it should be simple, but it’s not always obvious, especially on the level of a genetic network. Once we know the function, we also need to develop an understanding of more or less what the specifications are, so that we can assess whether a system satisfies those specs and in what way it deviates from them when perturbed. But how do you elucidate the functional specifications of a biological organism? For example, how precise does a gene expression pattern need to be for an embryo to become an adult that works “well enough”? Perhaps we observe a certain range of parameters or patterns in a wild population, but does that cover the whole range that could be tolerated with minimal consequences for fitness? Importantly, how does tolerance depend on other parts involved in the system? Maybe single parts can deviate by some level from the norm without disturbing the system too much, but how many parts can vary and by how much before the system “fails”? What do intermediate “failures” look like? How does this depend on the environment in which the system needs to operate? These kinds of questions bridge multiple levels of biology, from molecular biophysics to population genetics, and I believe they can be approached quite productively from an engineering standpoint.

What do you find most challenging about research or interdisciplinary work?

I find interdisciplinary research to be extremely rewarding, both because I like learning about many different areas and because I enjoy seeing the way people with formal training in those areas approach the same problems with unique insights and methods. However, this diversity can also make the work very challenging, because not everyone agrees on how to value or evaluate various pieces of evidence, or even on what’s considered acceptable or sufficient to support a conclusion. For this reason, there are few established standards for how to validate results, which means you have to get comfortable generating the justification yourself. That both the methods and the results draw from disparate sources also means it can be hard to find readers who can understand or engage with the work as a whole, so you really have to try hard to communicate clearly and precisely, and learn how to balance accessibility for a broad audience with enough detail to satisfy specialists in each of the areas you touch.

How would you describe the results of a recent paper you contributed to?

I had a preprint come out recently in collaboration with Jiaxi Zhao, Matthew Norstad, and Hernan Garcia at UC Berkeley. We investigated a gene called fushi tarazu (ftz) that is expressed in a seven-stripe pattern in early fruit fly embryos. It’s known that ftz is autoregulatory, meaning the Ftz protein binds its own enhancer to promote its own expression levels. The positive autoregulatory “motif” is present in many genetic networks responsible for deciding cell fate during embryonic development, and it’s thought this is because the motif can act as a binary “switch” whose ON or OFF state is set by the action of transient upstream regulatory factors. This means, in effect, that it can remember a cell fate decision. Despite the prevalence of this module in nature, it’s been very difficult to show in vivo that it is bistable, which is the mathematical property of a dynamical system that allows it to act as a switch. We performed live-imaging experiments to simultaneously measure ftz transcription and Ftz protein levels in developing fruit fly embryos. We found that upstream regulatory factors transiently drive ftz expression and that ftz autoregulation becomes active at a specific developmental time. Furthermore, we used our experimental setup to measure (not fit!) all the parameter values in a dynamical systems model of ftz regulation, from which we could make quantitative predictions for ftz expression levels in individual nuclei. Our model shows that the ftz autoregulatory module is indeed bistable, and we performed some additional in silico analysis on the model to show that the cell fate decision to have Ftz ON or OFF is made in about 30 min. I think the work is a wonderful blend of experiment with theory, and a case where mathematical modeling can make some pretty accurate predictions for a biological system.

What do you like to do in your spare time outside of work?

I have a creative side that I indulge with writing, drawing, and (when I have time for it) playing the viola and piano. I grew up in Colorado, so I also love hiking or camping in the mountains, especially during the summer. Since I moved to Germany for my postdoc, I’ve also been trying to improve my German, which sometimes feels even harder than my research! But I’m having fun.